Exploring the European Union’s Just Transition Policy: Evolution, Reach, and Future Directions

Elena Šiaudvytienė

Today, climate policy actors and scholars are shifting their focus onto factors that could speed up climate action because most countries are failing to deliver on their promises regarding the Paris Agreement (UNEP, 2022), and humanity keeps breaking ever-new wrong records on climate change (UNEP, 2023). The Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2023) and COP28 (UNFCCC, 2023) pointed to just transition as one of these crucial factors. In the European Union (EU), the Belgian Presidency of the first half of 2024 has put just transition “at the heart of its priorities” (Council of the European Union, 2023, p. 4). Although there are different definitions of just transition, the International Labour Organization (ILO) provides a globally accepted one in its Guidelines for a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all (ILO, 2015). According to the document, just transition is a process “towards an environmentally sustainable economy” that “needs to be well managed and contribute to the goals of decent work for all, social inclusion, and the eradication of poverty” (ILO, 2015, p. 4). The just transition approach assumes that considering the negative social impacts of environmental transitions is the right thing to do and (therefore) can avoid political backlash and social conflicts (Heyen et al., 2021). It is becoming increasingly clear that achieving the net-zero goal by 2050 will be impossible without good just transition policies. The EU’s just transition policy is noteworthy as it exemplifies the first regional-level implementation of such an approach. Therefore, I aim to explore and assess the emerging EU’s just transition policy framework in this article, drawing on EU legislation and secondary scholarly literature. First, I will give an overview of the origins of the EU's just transition policy and how it is implemented through the European Green Deal (EGD) framework. Then, I will compare the EU’s and the International Labour Organisation’s (ILO) approaches to just transition. Afterward, I will describe and briefly assess the four main elements of the EU’s just transition policy framework.

- The EU’s Just Transition Policy: Origins and the European Green Deal Framework

Just transition policy in the EU is shaped under the EGD framework, presented by the European Commission (EC) in December 2019 and approved in January 2020. The EGD Communication from the Commission states that the EGD is “a new growth strategy that aims to transform the EU into a fair and prosperous society, with a modern, resource-efficient and competitive economy where there are no net emissions of greenhouse gases in 2050 and where economic growth is decoupled from resource use” (European Commission 2019, p. 2). Such a process of transformation is called the green transition.[1] As the EU acknowledges, it should be pursued in a “socially just manner” (Sabato et al. 2023, p. 7).

The adoption of the EGD is probably the most significant policy shift in the EU in recent years. For the first time, the ecological transition moved to the top of the EU policy agenda, which contrasted “starkly with the disastrous austerity agenda pursued by the previous Juncker Commission” (Matthieu 2022, p. 151). The EGD responded to the widespread urgency displayed in public opinion, and to the calls from the scientific community and civil society. Right before the presentation of the EGD, the European Environmental Agency (EEA) (European Environment Agency, 2018) and Eurostat’s analysis of progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Eurostat, 2018) indicated that “the policy of the two previous Commissions [had] failed to meet objectives and that a new approach must be taken” (Charveriat 2023, para. 3). The change of course was also demanded by civil society organizations such as the European Environmental Bureau (EEB), Climate Action Network Europe (CAN Europe), and Think2030. Moreover, the EU opted for a unilateral approach to climate policy because of some international realities of that time: the election of Donald Trump in 2016 and the US withdrawal from the Paris Agreement in 2017, as well as the loss of competitiveness in the area of environmental goods in the EU. The need and commitment to unilateral climate action through the EGD was strengthened even more when the COVID-19 pandemic exposed “the EU’s lack of autonomy in certain key sectors and value chains for both its economy and decarbonization” (Charveriat 2023, para. 16). Finally, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine caused an energy crisis in Europe and highlighted the even more urgent need to shift to renewable energy sources.

The EGD and its just transition policy package resulted from a political synthesis involving compromises between the EU institutions and member states (Charveriat, 2023; Crespy & Munta, 2023). According to Hoon and Pype (2022), theoretically, the EGD should be contextualized in three main discourses: the concept of the just transition as proposed by the international labor organizations, the so-called “Green New Deal (GND) economics” of the 1990s, and the principles of liberal market economics (pp. 7-8). The GND strand of economics maintains that every sound economic policy must include social and ecological objectives. As in “Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal, GND economics suggest a government-led investment plan that, especially in times of crisis, can generate secure and quality employment through efforts to improve public infrastructure and welfare standards” (p. 7). Such an approach rests on the same assumptions as the green growth vision, which, contrary to degrowth economics (Hickel, 2020; Šiaudvytienė, 2023), sees economic growth and development as vehicles for social and ecological justice. Finally, with its reliance on carbon pricing as the main instrument to achieve economic and societal adjustment, the EGD “trusts in the free market to adjust and react to price incentives, to transition to a zero-emission economy without changing its foundations” (Hoon and Pype 2022, p. 8).

In the EU context, the idea of the just transition is not new. According to Matthieu (2022), back in 1951, “the European Coal and Steel Community created a ‘Fund for the training and redeployment of workers’” (p. 154), which could have inspired European just transition proposals in the environmental sphere in the same way as Mazzochi’s proposed just transition idea in the 1970s was inspired by the “Superfund for workers”. However, in Europe, the idea of a just transition did not receive more attention because of the increasing dominance of market liberalism in the development of the EU project. The idea of the just transition appeared on the EU policy agenda again and was introduced into the EGD thanks to the international labor movements, which brought it from the US context to the level of international organizations. After the just transition was embraced by the ILO and recognized in the Paris Agreement, “it found its way into the EU’s Energy Union and a newly created Platform for Coal Regions in Transition in 2017” (Matthieu 2022, p. 154). Right after that, the European Parliament proposed a Just Transition Fund in 2016 and reiterated it in 2018, within the framework of the Multiannual Financial Framework for the period 2021–2027. Then, a just transition policy was approved and the EGD adopted by the Council in December 2019 (Marty 2020).

- Comparing the ILO’s and the EU’s Just Transition Approaches

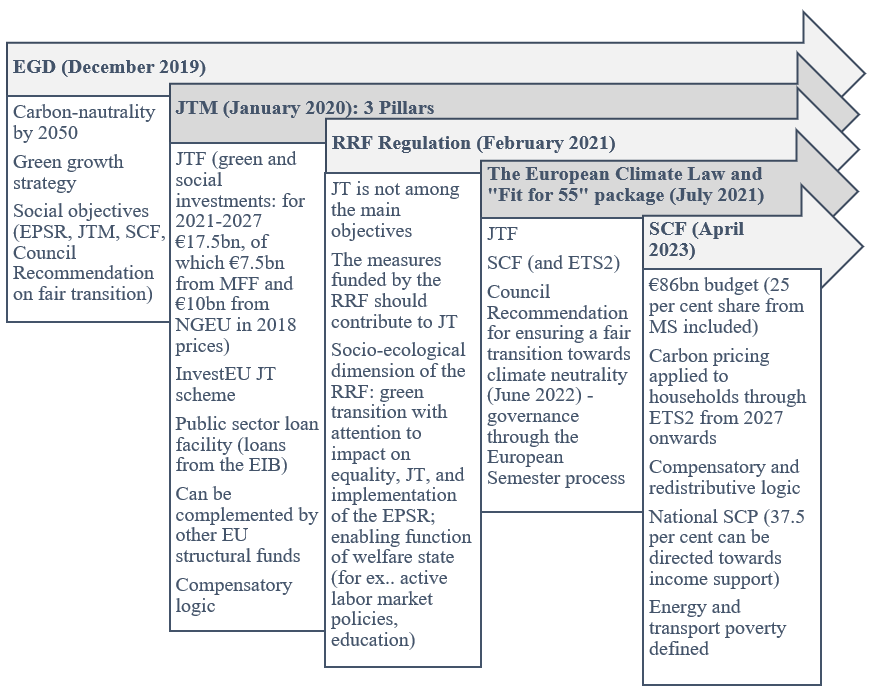

Since the concept of just transition in the EU emerged from the context of international organizations and especially from the Paris Agreement and the ILO’s agenda, it “show[s] a certain degree of correspondence with the main elements of the just transition framework proposed by the ILO in their 2015 Guidelines” (Sabato and Fronteddu 2020, p. 15). However, the EU’s vision of just transition differs from the ILO’s approach in some significant ways. In general, according to Crespy and Munta (2023), “the EU's vision is far less ambitious than that promoted by the ILO in three main respects: the underlying philosophy, the policy-making tools, and the political processes” (p. 4). The authors point out that, regarding the philosophy, the ILO promotes a just transition centered on distributive and procedural justice. In contrast, the EU’s just transition framework has no real options for citizens to participate. It is formed and implemented from the top and seems worried only about a possible political backlash. Looking at policy-making, the ILO’s vision of a just transition embraces a comprehensive and integrated approach and aims to bring together different levels of action (local and global) and policies in areas like the economy, society, and the environment. On the contrary, the EU just transition notion is a part of the EGD strategy, “conceived as a new growth model meant to be sustainable from an environmental point of view” (ibid.). Therefore, the specific policies came later, and the EU's transition policy framework (as illustrated in Figure 1) is still in the making and “gradually emerging, made up of legislation, funds, guidelines and recommendations” (Sabato et al. 2023 p. 20). Finally, regarding political processes, EU just transition politics does not demonstrate social consensus, as recommended by the ILO, but is characterized by heated debates over the allocation of national funds, the green taxonomy, and many other essential aspects of the EU just transition policy.

Figure 1

The EU Just Transition Policy Framework

Note. From Author, based on Crespy and Munta (2023) and Sabato et al. (2023)

Another comparison between the ILO’s and the EU’s approaches to just transition can be made using the distinction in Alcidi et al. (2022) between a compensatory and an integrated logic that can underpin eco-social policies. In the compensatory logic, “social policy objectives and tools are linked to environmental objectives and tools only by the extent to which the latter produces negative externalities.” While in the integrated logic, “social policies and goals are designed together with ecological objectives and goals” and welfare policies “do not only compensate for the social costs of the green transition but they are also conceived as a necessary pre-condition to facilitate the ecological transition” (p. 188). According to Crespy and Munta (2023), the majority of the EU just transition policies are characterized by compensatory logic since they target “narrow groups of transition ‘losers’” (p. 4). On the other hand, the ILO’s approach is guided by an integrated logic.

- Components of the EU’s Just Transition Policy

As mentioned earlier, the EU’s just transition framework is steadily taking shape by introducing new initiatives over the years (Sabato & Mandelli, 2023). This framework has three main components: the Just Transition Mechanism, the Social Climate Fund under the “Fit for 55” legislative package, and the Council Recommendation on Fair Transition (Council of the European Union, 2022). Furthermore, the EU's recovery from COVID-19 agenda, known as the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF), plays a significant role in supporting the EU's just transition policy, even though it is not its primary objective.

Besides transforming Europe into the first climate-neutral continent by 2050, the EGD also has social objectives and aims to achieve a just transition. It promises to “leave no one behind” (European Commission 2019, p. 16) and address the social and economic consequences of the green transition. As part of the Sustainable Europe Investment Plan (SEIP) (also known as the European Green Deal Investment Plan), the Commission introduced the Just Transition Mechanism (JTM) in January 2020, embedded in the cohesion policy and serving as a central tool to fulfill the social objectives of the European Green Deal (EGD). The JTM initiative has three pillars: a Just Transition Fund (JTF), “the use of a fraction of InvestEU financing for climate objectives and the creation of a public sector loan facility at the European Investment Bank, partly guaranteed by the EU budget” (Cameron et al. 2020, p. 10). At the same time, in a communication entitled “A Strong Social Europe for Just Transitions” (European Commission, 2020), the EU made its first attempt “to connect EGD governance with existing social policy instruments, especially the European Pillar of Social Rights (EPSR)” (Crespy and Munta 2023, p. 3), even though, the EPSR addresses socio-ecological problems only minimally. In general, the implementation of the EGD is now driven by the already mentioned “Fit for 55” package, which was proposed by the European Commission in July 2021 and adopted by the European Parliament and the Council of the EU in April 2023. It refers to the EU’s target of reducing net greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by at least 55% by 2030. In it, the JTF and the Social Climate Fund (SCF) specifically address the problems of inequality and social justice related to decarbonization in the EU.

3.1 The Just Transition Mechanism

The core pillar of the Just Transition Mechanism is the Just Transition Fund (JTF). The JTF has a budget of €17.5 billion (calculated based on 2018 prices) for 2021-2027. This allocation comprises €10 billion from the Next Generation EU (NGEU) program and €7.5 billion from the multiannual financial framework (MFF) for 2021-2027. The JTF “focuses on the regions that are most affected by the transition given their dependence on fossil fuels, including coal, peat and oil shale or greenhouse gas-intensive industrial processes, and that have less capacity to finance the necessary investments” (European Commission n.d., para. 6). In order to access funding from the JTF, Member States must commit to the 2050 EU climate neutrality target. If a member state does not make this commitment, “only 50% of the annual allocations for that Member State […] shall be made available for programming and included in the priorities” (European Union 2021a, art. 7.1). Additionally, member states have to prepare their Territorial Just Transition Plans (TJTP), based on the principle of partnership with local and regional governments and relevant stakeholders and submit them to the European Commission. These plans should identify the eligible territories expected to be the most negatively impacted by the transition to a climate-neutral economy and “outline the specific indicators intended to contribute to the selected JTF objectives” (Crespy and Munta 2023, p. 7). The JTF can be complemented by other structural funds such as the Cohesion Fund, the European Social Fund+ and the European Regional Development Fund.

Article 8 of the JTF Regulation lists the eligible activities the fund will support. These activities can be divided into green investments, which aim to diversify and modernize local economies, and social investments, which should help mitigate the negative repercussions of the transition on employment. As for the first category, the JTF Regulations mention investments in economic diversification, new businesses, research and innovation, clean energy infrastructure, energy efficiency, smart and sustainable local mobility, digitalization, the circular economy, water decontamination, and land restoration. On the other hand, the JTF-funded social activies include the upskilling and reskilling of workers and job seekers, job-search assistance, the active inclusion of jobseekers, technical assistance, investments in infrastructure for training centers, child- and elderly-care facilities, gender equality, exceptional attention to vulnerable groups (such as disabled workers), and the reduction of energy poverty. Furthermore, Article 9 of the JTF Regulations lists activities that will not be funded: the decommissioning or the construction of nuclear power stations; the manufacturing, processing, and marketing of tobacco and tobacco products; and investments in fossil fuels.

While the governance of the first pillar happens through shared management between the EU and member states, the other two pillars of the JTM are managed directly by the EU institutions and implementing partners (CEE Bankwatch Network, 2023). They include just transition initiatives within InvestEU and a public sector loan facility, integrating member state co-financing, EU grant support, and European Investment Bank (EIB) loans. The second pillar, the InvestEU program, seeks to foster sustainable investment, innovation, and job creation in Europe by leveraging a EUR 26.2 billion EU budgetary guarantee to support implementing partners such as the EIB Group, national development banks, and others, aiming to catalyze €372 billion worth of investments during the 2021 to 2027 funding cycle, from which about €10-15 billion is expected to be mobilized through a dedicated Just Transition Sheme (CEE Bankwatch Network, 2023). InvestEU supports investments in four policy windows: “sustainable infrastructure; research, innovation and digitisation; SMEs; and social investment and skills” (European Union 2021a, rec. 27). Furthermore, the InvestEU Just Transition Scheme (JTS) funds projects only in these territories, and in these sectors and activities that are listed in the relevant TJTPs, prepared in order to receive funds from the first pillar of the JTM. Projects not located in the Just Transition (JT) regions will be able to benefit from the InvestEU JTS “if funding of the project is key to the development of a JT region” (Chraska 2023, p. 5).

To conclude, the second pillar of the JTM differs from the first in its sources of funding, as well as in its scope of support. The JTF’s “main emphasis is on counteracting negative economic impacts of the green transition in carbon-intensive regions – like unemployment, brain drain, and social issues – through economic diversification, reskilling workers and actively including workers and jobseekers” (CEE Bankwatch Network 2023, 4). On the other hand, the InvestEU JTS will support “a broader range of projects, including renewable energy sources, energy efficiency schemes, energy and transport infrastructure, gas projects, district heating, decarbonisation, social infrastructure and economic diversification” (ibid.). Unlike the other 2 JTM pillars, the InvestEU program allows fossil-fuel-related investments.

The third pillar of the JTM, the public sector loan facility, “is made up of EUR 1.5 billion in grants from the EU budget and EUR 10 billion in loans from the EIB Group”, which “should be used together’ (CEE Bankwatch Network 2023, p. 3). The public loan facility will predominantly fund significant infrastructure projects carried out by public authorities that lack adequate revenue streams for commercial financing, and these projects typically include energy and transport, district heating, energy efficiency (including building renovation), and social infrastructure initiatives (European Commission, n.d.-b).

3.2 The Social Climate Fund

The second instrument of the EU just transition policy framework is the Social Climate Fund (SCF). The European Commission put it forward in July 2021 as a component of the “Fit for 55” package, scheduled to commence in 2026. The SCF was proposed only after the adoption of the European Climate Law in 2020 as a response to “widespread criticism that the Commission failed to provide adequate support for more vulnerable consumers who could face the greatest difficulties in managing high energy costs” (Matthieu, 2022, p. 158). The SCF Regulation (European Union, 2023) was approved in April 2023. The SCF builds upon the Emissions Trading System (ETS) by expanding it to encompass buildings and transport systems (ETS2). This extension will introduce carbon pricing for households beginning in 2027, leading to a potential price increase.

Consequently, the SCF will offset “the negative impact on the most vulnerable individuals and small companies by providing resources for Member States to grant direct income support and fund investments in clean housing and transport” (Crespy and Munta 2023, p. 10). Moreover, the SCF Regulation provides the first institutional definition and usage of energy and mobility poverty concepts. The agreed budget for the SCF is €65 billion, and an additional share of 25% from member states must be added, resulting in a total budget of €86 billion.

In order to access the funding from the SCF, the EU member states will need to prepare their national Social Climate Plans (CSPs) with “qualitative ‘milestones’ and quantitative ‘targets’ […] to be achieved by July 2032” (Crespy and Munta 2023, p. 11). The drafting of the CSPs must happen after consultations with “local and regional authorities, economic and social partners, and civil society” (Sabato et al., 2023, p. 24). According to the SCF Regulation, each CSP should “contain a coherent set of existing or new national measures and investments to address the impact of carbon pricing on vulnerable households, vulnerable microenterprises, and vulnerable transport users in order to ensure affordable heating, cooling, and mobility, while accompanying and accelerating necessary measures to meet the climate targets of the Union” (European Union 2023, art. 4.1). Hence, the SCF is both, compensatory and redistributive: it will provide (temporary) direct income support (at the beginning – up to the maximum of 37.5% of the available funding) as well as help “vulnerable households, vulnerable micro-enterprises, or vulnerable transport users” (art. 6.1e) with long-lasting structural investments in “technical measures to mitigate environmental risks” (Crespy and Munta 2023, p. 10), such as energy efficiency, building renovations, zero- and low-emissions mobility and transport, and decarbonization. Finally, in Annex I, the SCF Regulation lists the criteria for allocating the funding to member states. They include the population at risk of poverty living in rural areas (2019); carbon dioxide emissions from fuel combustion by households (2016-2018 average); the percentage of households at risk of poverty with arrears on their utility bills (2019); total population (2019); the Member State's gross national income (GNI) per capita, measured in purchasing power standard (2019); and the country's dependency on fossil fuel. Thus, the SCF seeks to address inequalities within and between countries.

3.3 The Council Recommendation on a Fair Transition

The third component of the EU just transition policy framework is contained in the 2022 Council Recommendation on ensuring a fair[2] transition towards climate neutrality (Council of the European Union, 2022). The EU introduced this non-binding social initiative, responding to criticism about the weakness of the EGD social dimension and the fragmented nature of the EU's just transition efforts. Hence, the Recommendation repeats the principle that nobody should be left behind in the transition to sustainability and identifies the “people and households that are most affected by the green transition, notably by job losses but also by changing working conditions and/or new task requirements on the job, as well as those subject to adverse impacts on disposable incomes, expenditure, and access to essential services” (Council of the European Union 2022, rec. 17). Importantly, the document invites policymakers to pay special attention to people “who are already vulnerable (i.e., irrespective of the transition), such as low- and lower-middle income households” (Sabato et al. 2023, pp. 24-25), people living in or at risk of energy poverty and mobility poverty, and “households headed by single parents” (Council of the European Union 2022, rec. 17).

Furthermore, the Recommendation on fair transition calls for member state governments to adopt a more integrated and participatory approach towards the just transition, which is somewhat closer to the ILO’s Guidelines for a just transition. It states that there is a need to “enhance the design of policies in a comprehensive and cross cutting manner and to ensure the coherence of spending efforts, at Union and national level” (Council of the European Union 2022, rec. 16). As summarized by Sabato et al. (2023), all well-designed fair transition “policy packages should include measures ensuring: i) active support to quality employment; ii) quality and inclusive education, training and lifelong learning, as well as equal opportunities; iii) fair tax-benefit systems and social protection systems, including social inclusion policies; and iv) access to affordable essential services and housing” (p. 25). The Recommendation indicates that the progress of its implementation will be reviewed “in the context of multilateral surveillance in the European Semester” (Council of the European Union 2022, art. 11g), which is the European Union's framework for the coordination and surveillance of economic and social policies (European Commission, n.d.-a). This review involves collaboration with relevant committees of the Council of the EU, such as the Employment Committee (EMCO) and the Social Protection Committee (SPC), along with other committees in their respective areas of expertise, like the Economic Policy Committee (EPC). According to the Recommendation, it should build upon existing scoreboards and monitoring frameworks, and additional indicators may be included, if necessary, with close cooperation with member states.

3.4 The Recovery and Resilience Facility

The fourth element of the EU just transition policy framework is the Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF). A just transition is not the primary goal of the RRF. However, according to the RRF Regulation (European Union, 2021), the member states must guarantee that the measures financed by the Facility contribute to achieving a just transition. The RRF is organized into six core policy areas (pillars) essential for recovering from the COVID-19 crisis and for strengthening the EU and its member states’ long-term resilience. The policy pillars illustrate environmental (green) and societal (social) aspects within the RRF; these two dimensions sometimes intersect. Hence, the socio-ecological dimension of the RRF can be identified when member states are obligated to consider the social aspects and equality impacts during the implementation of the green transition, requiring them to allocate a minimum of 37% of the RRF expenditure to green transition measures in their Recovery and Resilience Plans (RRPs). The RRF also requires that the national RRPs contribute to “the implementation of the European Pillar of Social Rights” (European Union 2021, rec. 39). Furthermore, the RRF highlights the importance of active labor market policies, education, training, and skills development policies and connects them to the implementation of the green transition. Next, in the RRPs, “building-renovation schemes to improve energy efficiency should include welfare infrastructure such as social housing, hospitals, schools, and other public buildings” (Sabato et al. 2023, p. 22).

Concluding Observations

Summarizing the scholarly observations about the EU just transition policy framework, several points of concern can be mentioned. First, despite the very inclusive vocabulary of the EU’s political discourse (Andersen et al., 2023), analysts find the EU approach to the just transition too narrow (Guillén & Petmesidou, 2021), restricted to the specific industries, groups, and territories most affected by decarbonization (as in the JTF), and not “to meet the vast social (and health) impact of the climate crisis on whole societies and to ensure social equity and inclusiveness” (Crespy and Munta 2023, p. 8). Therefore, so far, the EU's transition agenda seems fragmented and does not “offer the comprehensive policy platform that the EU needs to deal with the impacts of the transition on affected workers, regions and vulnerable individuals” (Akgüç et al. 2022, p. 1), and leaves significant aspects regarding inequality and the distribution of environmental risks unaddressed. According to Sabato and Fronteddu (2020), this also happens because the EGD sets “no clear priorities among environmental, economic, and social should trade-offs arise" (p. 13) and follows an economic framing (Cigna et al., 2023). Second, even though EU just transition policy regulations call on the member states to apply a participatory approach in designing and implementing just transition policies, it is not mandatory. Consequently, just transition policies are often seen as implemented following the EU top-down approach. Lastly, the Recommendation on fair transition, while endorsing a more integrated approach, is non-binding, and its monitoring relies on the European Semester, a tool that has not been reformed adequately to monitor the implementation of just transition policies effectively.

Consequently, in further developing the EU's just transition policy framework, it will be crucial to broaden the scope and inclusivity of the policy and address the broader impacts of the climate crisis and the green transition. Moreover, the EU's just transition policy would significantly improve if made more comprehensive, aligning well with one of the objectives of the Belgian Presidency of the Council in the first half of 2024. Next, as recommended by the ILO, a just transition should extend beyond strict economic framing and incorporate the social and health impacts of environmental policies more effectively. Such a way of seeing would imply, for example, a more robust integration of these impacts into the policy framework. Finally, it would also necessitate a discussion about strengthening the binding nature of the EU's just transition policy and establishing effective mechanisms for the monitoring of its implementation.

References

Akgüç, M., Arabadjieva, K., & Galgoczi, B. (2022). Why the EU’s patchy ‘just transition’ framework is not up to meeting its climate ambitions. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4220500

Alcidi, C., Corti, F., Gros, D., & Liscai, A. (2022). Towards a socially just green transition: The role of welfare states and public finances. In Greening Europe. 2022 European Public Investment Outlook. Open Books Publishers.

Andersen, A. S., Hauggaard-Nielsen, H., Christensen, T. B., & Hulgaard, L. (2023). Interdisciplinary perspectives on socio-ecological challenges: Sustainable transformations globally and in the EU. Taylor & Francis.

Cameron, A., Claeys, D. G., Midőes, C., & Tagliapietra, D. S. (2020). A Just Transition Fund—How the EU budget can best assist in the necessary transition from fossil fuels to sustainable energy. Policy Department for Budgetary Affairs Directorate General for Internal Policies of the Union.

CEE Bankwatch Network. (2023). The second and third pillars of the Just Transition Mechanism. CEE Bankwatch Network. https://bit.ly/3tizutB

Charveriat, C. (2023). The Green Deal: Origins and evolution. Green, 3(3). https://bit.ly/3v8fcmW

Chraska, F. (2023). Just Transition Mechanism. Pillar 2&3. Kick-off Event - Just Transition, Megapoli. https://bit.ly/477ZQfm

Cigna, L., Fischer, T., Hasanagic Abuannab, E., Heins, E., & Rathgeb, P. (2023). Varieties of just transition? Eco-social policy approaches at the international level. Social Policy and Society, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1474746423000192

Council of the European Union (2022). Council Recommendation on ensuring a fair transition towards climate neutrality, 9107/22. The Publications Office of the EU. https://t.ly/5ITNt

Council of the European Union. (2023). Programme of the Belgian Presidency of the Council of the EU. First half of 2024. Council of the EU. https://bit.ly/47nBwXn

Crespy, A., & Munta, M. (2023). Lost in transition? Social justice and the politics of the EU green transition. Transfer, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/10242589231173072

European Commission (2019). The European Green Deal. Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the European Council, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, and the Committee of the Regions, COM (2019) 640 final. European Commission. https://t.ly/FO7H2

European Commission. (2020). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee, and the Committee of the Regions. A Strong Social Europe for Just Transitions. European Commission. https://t.ly/sEm7o

European Commission. (n.d.). Just Transition Fund. Internal Market, Industry, Entrepreneurship and SMEs. https://bit.ly/3Ou3Elm

European Commission. (n.d.-a). The European Semester explained. An explanation of the EU’s economic governance. https://bit.ly/3RRa1Rq

European Commission. (n.d.-b). The three pillars of the Just Transition Mechanism. Just Transition Mechanism. https://bit.ly/3ND1oaC

European Environment Agency. (2018). Environmental Indicator Report 2018 In support of monitoring the Seventh Environment Action Programme , EEA Report, No 19/2018. EEA. https://bit.ly/470vixE

European Union. (2020). Regulation (EU) 2020/852 of the European Parliament and of the Council on the establishment of a framework to facilitate sustainable investment, and amending Regulation (EU) 2019/2088, Official Journal of the European Union, L 198/13. The Publications Office of the EU. https://bit.ly/47nBcYF

European Union. (2021). Regulation (EU) 2021/241 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 12 February 2021 establishing the Recovery and Resilience Facility. The Publications Office of the EU. https://bit.ly/4auOZz3

European Union. (2021a). Regulation (EU) 2021/1056 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 24 June 2021 establishing the Just Transition Fund. Official Journal of the European Union, L 232/1. The Publications Office of the EU. https://bit.ly/3Y9vHd2

European Union. (2023). Regulation (EU) 2023/955 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 10 May 2023 establishing a Social Climate Fund and amending Regulation (EU) 2021/1060. The Publications Office of the EU. https://t.ly/wsQKH

Eurostat. (2018). Sustainable development in the European Union. Monitoring report on progress towards the SDGs in an EU context, 2018 edition. Publications Office of the European Union. https://bit.ly/44A51ob

Guillén, A., & Petmesidou, M. (2021). A greener and more social pillar. https://t.ly/Ll6Kq

Heyen, D. A., Beznea, A., Hünecke, K., & Williams, R. (2021). Measuring a Just Transition in the EU in the context of the 8th Environment Action Programme: An assessment of existing indicators and gaps at the socio-environmental nexus, with suggestions for the way forward. Oeko-Institut e.V. and Trinomics. https://bit.ly/3KKdVqx

Hickel, J. (2020). Less is more: How degrowth will save the world (1st edition). Cornerstone Digital.

Hoon, L., & Pype, K. (2022). How can the EU deliver a socially just green deal? Looking at the European Green Deal through a just transition lens. Open Society Foundations. https://bit.ly/3RQEz5E

ILO. (2015). Guidelines for a just transition towards environmentally sustainable economies and societies for all. ILO. https://bit.ly/3mGSMFB

IPCC (2023). Summary for policymakers. In Core Writing Team, H. Lee and J. Romero (eds.), Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II, and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC, 1-34. https://t.ly/u-N9f

Marty, O. (2020). What should we make of the Just Transition Mechanism put forward by the European Commission? Policy paper: European issues n°567. Foundation Robert Schuman. https://t.ly/rqbpG

Matthieu, S. (2022). The European Green Deal as the new social contract. In Holemans, D. (ed.). A European just transition for a better world. Green European Foundation.

Robins, N. (2022). The just transition: shaping the delivery of the inevitable policy response. https://bit.ly/3A4kIq0

Sabato, S., & Fronteddu, B. (2020). A socially just transition through the European Green Deal? Working Paper 2020.08. ETUI. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3699367

Sabato, S., & Mandelli, M. (2023). Towards an EU framework for a just transition: Welfare policies and politics for the socio-ecological transition. European Political Science. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-023-00458-1

Sabato, S., Büchs, M., & Vanhille, J. (2023). A just transition towards climate neutrality for the EU: debates, key issues and ways forward. Background paper commissioned by the Belgian Federal Public Service – Social Security, OSE Paper Series, Research Paper No. 52. European Social Observatory. https://bit.ly/3tsgaKh

Šiaudvytienė, E. (2023). The argument for economic degrowth in the encyclical letter Laudato si’. Oikonomia, 22(1), 17–20. https://oikonomia.it/images/pdf/2023/febbraio/06-elena.pdf

Tomassetti, P. (2022). From justice to fairness? ETUI News. https://www.etui.org/news/justice-fairness

UNEP (2022). Emissions Gap Report 2022: The Closing Window — Climate crisis calls for rapid transformation of societies. Nairobi. https://www.unep.org/emissions-gap-report-2022

UNEP (2023). Emissions Gap Report 2023: Broken Record – Temperatures hit new highs, yet the world fails to cut emissions (again). Nairobi. https://doi.org/10.59117/20.500.11822/43922

UNFCCC (2023). First global stocktake: Proposal by the President. Outcome of the first global stocktake (Draft decision FCCC/PA/CMA/2023/L.17). UNFCCC. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/cma2023_L17_adv.pdf

[1] In the EU vocabulary, "green transition" means "the transition of the Union economy and society towards the achievement of the climate and environmental objectives primarily through policies and investments, in accordance with the European Climate Law […], the European Green Deal and international commitments" (Council of the European Union, 2022). Here “the climate and environmental objectives” refer to climate change mitigation; climate change adaptation; the sustainable use and protection of water and marine resources; the transition to a circular economy; pollution prevention and control; and the protection and restoration of biodiversity and ecosystems that are listed by Regulation (EU) 2020/852 (European Union, 2020).

[2] Traditionally, international organizations and actors, the EU included (the EGD, for example), have used the term ‘just’ transition. However, in the recent Council Recommendation on ensuring a fair transition towards climate neutrality, the EU started to refer to ‘fair’ transition instead. According to Sabato et al. (2023), "according to interviews conducted with European Commission officials, 'just' and 'fair' transition has the same meaning: the latter notion was introduced in order to better align just transition (from a terminological point of view) with the 'fairness' dimension of 'competitive sustainability,' a notion central to EU socio-economic governance since 2020" (p. 7). On the contrary, Tomassetti (2022) does not agree that the change of the term was unintentional, criticizes the EU for "misciting the content of existing policy documents" (para. 3), and claims that the discourse on fairness may be subject to manipulation or lack meaningful discussion if justice is not taken into account as a fundamental principle of coexistence. In this chapter, both terms will be used interchangeably.

IT

IT  EN

EN